In criminal cases, wiretaps are conducted according to Title III, the wiretap statute. After charges are filed, the defendant gets copies of all the applications, affidavits and orders for the wiretap. They get copies of all intercepted conversations and seized records. They can move to suppress the seized conversations and records on a number of grounds. They can argue there wasn't probable cause for the interceptions or the Government didn't exhaust other, less intrusive investigative techniques before resorting to wiretaps. They can argue the Government didn't properly minimize innocent calls or didn't follow the court's orders on how to conduct the wiretap. While notice may be delayed, it can't be eliminated altogether.

With wiretaps and other electronic surveillance conducted for intelligence rather than law enforcement purposes, including those under FISA, the only reporting requirements are to how many applications were made and granted. (Similarly, under the Patriot Act, providers of records are gagged from informing those whose records were turned over. With Sneak and Peek searches, no notification is left at the time of the search.)

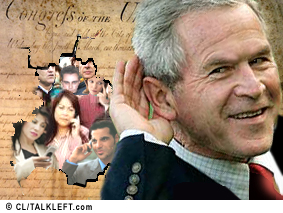

The Government, in amending FISA, like it did with the Patriot Act, is trying to make an end run around the 4th Amendment and its requirement of probable cause. This is particularly dangerous now that "the wall" has come down and intelligence agencies are allowed to share information with law enforcement agencies.

In our coverage of the FISA Amendment, let's not forget we also need the SAFE Act as well as some way for Americans whose calls are intercepted and whose records are seized, even if it's just for intelligence purposes, to go into court and challenge it after the fact. To do that, they need to know about it in the first instance.

A good start would be for Congress to pass a bill introduced back in 2003: The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Reporting Act of 2003. As the ACLU wrote to the bill's sponsors at the time:

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) authorizes secret wiretaps and secret searches of the homes and offices of Americans and other forms of data gathering for national security reasons. While the initial enactment of FISA was an appropriate accommodation of national security interests and individual rights to privacy and due process, since its initial enactment FISA has been expanded in ways that pose an increased threat to individual rights. Moreover, FISA surveillance authorities are now being used more and more; indeed, it appears that the federal government carries out more electronic surveillance under the authority of FISA than under criminal rules.

Given the absolute secrecy of FISA searches and seizures, mechanisms for public accountability are crucial to protect rights of privacy - as well as to insure effective and efficient use of this extraordinary authority. Your bill to require public accounting of the number of US persons subjected to surveillance under FISA, the number of times FISA information is used for law enforcement purposes, and to require disclosure of other information would be an important step in providing for oversight and public scrutiny of these extraordinary powers.

FISA judges rubber stamp secret FISA applications for eavesdropping so long as the application is filled out correctly. They don't weigh the merits of the request. There is no disclosure of whether the warrants produce useful information so Congress can make sure the power isn't being misused by the Executive Branch. All that has to be disclosed is the total number of applications made and how many were granted or refused.

The FISA Amendment excludes even more surveillance from the existing and paltry FISA reporting requirements. If Congress is going to fix FISA, it should increase the reporting requirements and loosen the gag restrictions and in both FISA and non-FISA intelligence surveillance cases, allow those who have been spied on to know about it at some point so they can challenge it and seek appropriate relief in a court of law.